The small town in which I lived had finally shaken off the residual leftovers of winter, leaving us residents joyfully rejoicing in a beautiful May spring. Like any eight-year-old, I was eager for school to end so I could have access to my friends at all hours of the day. Being the only one of the group to be homeschooled, I can recall staring at the time on the digital clock over the stove for precisely 3:35, the time my friends’ school bus came.

The day of May 29, 2009, began like any other: waking up at 9 a.m., brushing my teeth, and trotting downstairs while still in my nightgown. After breakfast was served to my younger siblings and me, school began. I was eager to learn about all sorts of things. . . presidents, multiplication, bugs; whatever it was, I was all eyes and ears and ready to absorb it all. One of my favorite things about homeschool was that our mom tailored each lesson to our interests which made learning a fun adventure.

After my mother dismissed me from school for the day I raced outside, ringlets of brunette curls bouncing after me. The screen door slammed shut behind me as I let out a happy squeal. I was absolutely ecstatic at the warmth of the air pressing against my skin; The humidity weighed down on me like a thousand blankets.

Plopping down on the cement steps, I drew smiley faces with chalk to pass time until the bus arrived. Finally, after what seemed like years, the hulking yellow bus screeched to a stop a few houses down. The doors opened to release a parade of elementary kids wearing oversized backpacks decorated with popular animated characters. My friends, like usual, raced to greet me.

After the standard question “how was school?” was answered with the typical “horrible!” we began playing one of our several random games. The day’s selection had included an odd sort of truth or dare: if one refused their dare, they got a bop on the head with an empty coffee creamer bottle dug we’d out of the trash.

After a few rounds and several bops later, the game is interrupted by the arrival of the neighbor boys. Gingerly, I removed myself from the group to talk to one of the boys. I had decided to “like” him a few weeks prior because all of my friends had a boy they were fond of. Once you reach a certain age, boys do not have cooties anymore.

In the midst of our conversation (which I couldn’t recall now even if I were offered a million dollars,) I experienced the most excruciating pain I have ever, ever, ever felt. The blindingly intense pain, centered in my head, was overwhelming.

In the blink of an eye, everything became hazy and out of focus. I couldn’t concentrate on anything besides the murderous pain in my head. It was pushing, pulling, shoving its way to the front of everything like a blaring siren; it demanded to be noticed.

While the boy was still speaking, I clutched my head and whirled around, headed straight for the door. I left the poor neighbor boy mid-sentence but I could hardly care; manners were the last thing on my mind. I stumbled into the house, most likely leaving a mess in my wake.

“Mom! Dad!” I shrieked, clutching the side of my head. “Mom!”

Somehow, I managed to make it upstairs. I cannot recall stumbling up the steps, past the playroom, and into the bathroom. There, I found my Dad.

“Daddy!” I exclaimed, clutching my head. I let out a primal wail, my words beginning to slur. The world around me became muddled, my brain only processing the necessary details.

“Annie. Annie! Let’s get you some medicine and then you can go lie down, okay?” my dad reasoned, his voice steady. I nodded numbly, taking the three pink chewables in my trembling hand. I munched them down and swallowed quickly. The taste of bubblegum on my tongue was a stark contrast to the bile building up in the back of my throat.

My dad led me to my room and helped me get into bed. The pain was still there, persistent as a leaking faucet. Drip. Drip.

My dad headed out, presumably to find my mother. I stayed on the bed for all of thirty seconds before I couldn’t be still any longer. I tossed the blankets off of my shuddering body with a flourish and barreled out of bed. It was too much.

Drip.

“It

hurts!! Daddy, it hurts!” I shrieked. Both of my parents were there now, the

pair having realized that this was not an ordinary headache. Panic ensued in

the Harley household; the screaming of the oldest child played like an eerie

soundtrack over the horrific ordeal.

Somehow, I ended up in the living room. I was lying on the couch, flailing my arms and screaming my throat raw. My mother and father stood over my writhing body, stoic. They were speaking about me in frightened tones. I knew this. But nothing mattered now except the pain.

“Take her to the hospital.” a voice.

The pain.

“Too far,” another.

…the pain.

“The fire station?”

The pain!

The pain is all there ever was, and all there ever would be, and there was nothing paramount to the tragic, mind-numbing pain that I felt.

I soon became somewhat aware that I was being led outside, to the van. Its red exterior gleamed brightly in the sun. I knew if I were to touch it, it would be warm against my fingertips.

It was almost summer, I recalled melancholically. A vague thought crossed my mind: would I be alive that long? Long enough to swim in pools and have sleepovers and catch fireflies at dusk?

My legs weren’t really working right as I was ushered to the vehicle; it was as though my father was corralling around a lifeless mannequin. I was unaware that this would be the last time I walked for many weeks to come. After being buckled into my car seat, words filtered down into my muddied consciousness. To the fire station, they had said.

Was I on fire? Is that why I hurt, hurt so very much? I imagined my golden brown curls burning off until no hair remained.

It took less than two minutes to get to the station. At least, I think. Time was reduced to a meaningless, cruel device used only to measure my suffering. Once at the station, my dad hurried off to retrieve the firemen. I closed my eyes for a moment, a blink. Too soon, noises demanded my attention and my eyes fluttered open again. Firemen crowded the vehicle, their faces etched with worry. They were dressed just like on TV. Maybe this is TV, I thought as I allowed my eyes to drift shut again. This is TV and I am a pixel girl.

The idea was quickly tossed out when I realized pixel girls couldn’t feel pain.

Questions, so many questions. All of them directed at me. I heard words coming out of their mouths, but I couldn’t process them. They may as well have been speaking French. A single thought passed through my mind before I slipped into oblivion. It was simple, clear, and to the point.

I am going to die.

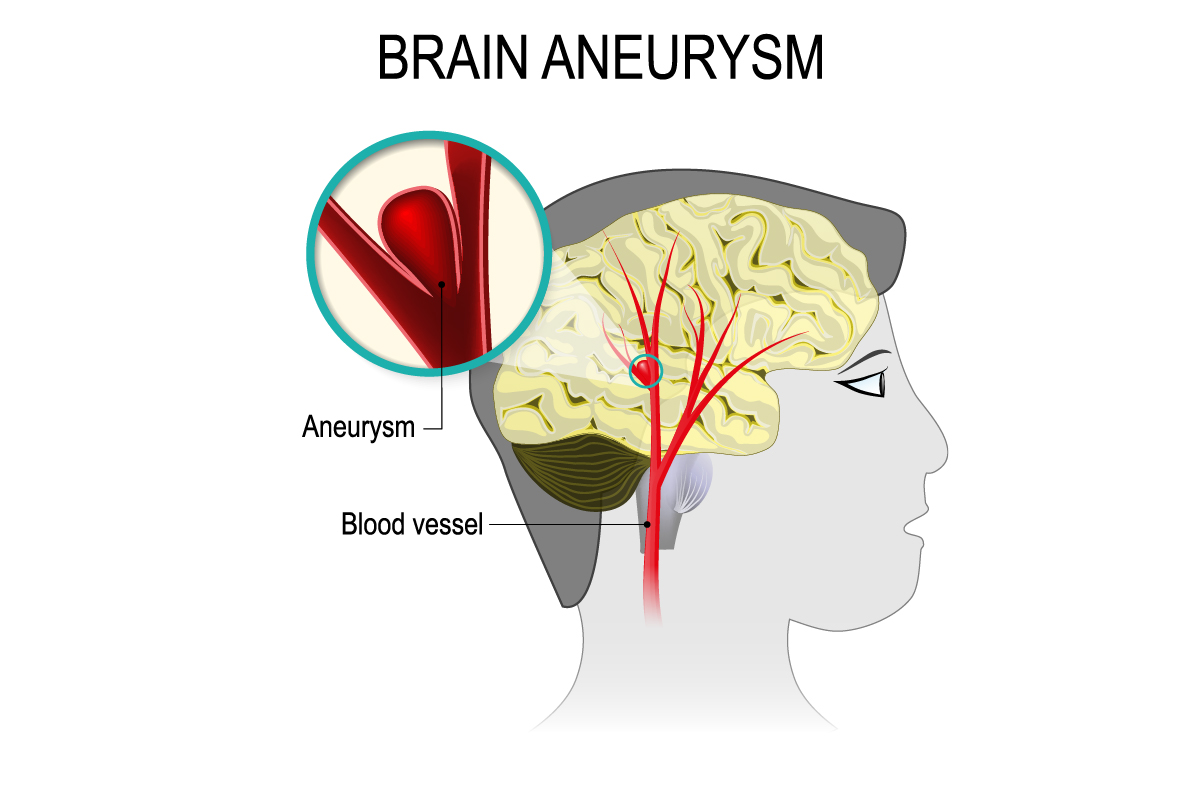

On that lovely day of May 29th, 2009, I suffered an aneurysm. A capillary in my brain burst which led to internal bleeding in my head. I was born with the defect; that weak capillary was destined to rupture from the moment I was born. This, it seems, was the source of the severe, instantaneous headache.

But nobody knew that yet.

Being in our van at the fire station is the last thing I can remember before the hospital. I can’t recall being wrestled out of my car seat, nor do I have any recollection of being transported to Saint Elizabeth’s Hospital in an ambulance. Under normal circumstances, I would have had to wait like any other patient. However, when I was in triage my parents brought up the game my friends and I were playing earlier in the day: a light hit on the head with a plastic container became a hit with a plastic pipe, which became a lead pipe. This misconception was likely instrumental in saving my life

I was rushed to get a CAT scan, and soon after the results came in the doctors discovered the bleeding. I was life-flighted to Pittsburgh Children’s Hospital for the surgery that would take place the following morning. My parents were terrified. The life of their daughter had suddenly been tossed skyward and only God was in the position to catch it. Once I was aboard the helicopter, my parents were left scrambling to find a babysitter for my younger siblings (ages five and one) and race me to the hospital. In an almost movie-like fashion, storms were brewing in the path of both my helicopter and my parent’s van.

I (thankfully) have no recollection of that helicopter flight. Not only was it through a line of thunderstorms, but I either stopped breathing or my heart stopped while up there. All I know is that the oxygen they were giving me wasn’t working and I needed to have a tube inserted down my throat to breathe.

I arrived at the hospital before my parents. They had a great deal of confusion in finding the hospital: it had just been rebuilt across town and Google and signs alike had yet to be updated.

Upon arrival, my parents were briefed on what was to happen next. I had to have surgery to remove the blood clotting in my brain. The invasive surgery was dangerous, but not doing anything was worse. My doctor had only performed one surgery of this type before, due to its rarity in children. Before long my parents had signed all of the necessary documentation, some of which had them agreeing to not hold the hospital responsible in the event of my death, and thus began the painful period of waiting. Updates and information was brought to my parents periodically. They were told that based on the location of the aneurysm I would have difficulty with math, vision, and balance. It was a small price to pay for my life.

The surgery was successfully completed on May 30, 2009. After 3 weeks I walked out of the hospital bald. It wasn’t fire that relieved me of my hair, no, but the scissors of a doctor preparing me for surgery. God has truly blessed me by saving me that day. There are so many minuscule things that could have gone wrong, but didn’t. For that, I am eternally grateful.

The effects of this traumatic experience are still with me in small ways, like my lack of peripheral vision on my right side and my slowness with math. I am constantly running into people and will always be eternally grateful to the calculator on my phone. Regardless of the struggle, I am a perfectly healthy 19-year-old woman.

There are days I’ll do something so utterly normal, things like calling my boyfriend on the phone, chasing my siblings around the house, or playing a song on my ukulele, and I just have to stop for a moment. Just stop and thank God that He saved me so I could live this life so that I can live in these mundane moments. Just stop and thank Him for intervening, for seeing that the gift of life was not snatched out of my fragile 8-year-old hands.

Life can change in an instant… I learned that young. Those changes can break us, or they can make us. If I were you, I’d go for the latter.

2009

2019

One response to “My Brain Aneurysm Survivor Story”

Yhat day is permanently etched in my memory. I wanted to take the pain from you and put it in my head. Somehow God calmed me down enough to do what had to be done. I can’t think of anything more painful in this world than the thought of your child dying (except maybe an Aneurysm). Thank God for the doctor and everyone else involved in your care. You have turned into a beautiful and smart young woman and I couldn’t be more proud of you.